“Urgent actions are required to address such substantial health impact and the associated environmental injustice in a warming climate,” the study concluded.

—

Air pollution caused by wildfires is attributable to more than 1.5 million deaths a year globally, albeit with significant geographical and socioeconomic disparities, a new major study has found.

The team of international scientists focused on fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and ozone (O3), two common toxic pollutants released by “landscape fires,” which include wildfires, controlled fires for land management purposes, and human-caused fires that spread over extensive areas of diverse landscapes.

Both pollutants pose severe health risks to humans and can lead to multiple health issues, including headaches, cardiovascular diseases, respiratory issues such as asthma, pneumonia, and lung cancer, and even premature mortality.

PM2.5, one of the most common and harmful components of air pollution, was linked to some 77.6% of the estimated 1.53 million annual deaths from fire-related pollution, while ozone accounted for 22.4%.

Low- and middle-income countries are disproportionately affected, accounting for over 90% of all attributable deaths with major hotspots in southeast Asia, south Asia, east Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. The latter alone accounted for nearly 40% of all deaths.

The countries with the highest death tolls were China, the Democratic Republic of Congo, India, Indonesia, and Nigeria.

Socioeconomic factors also play a role, with some groups at greater risk of experiencing negative health effects from fire pollution than others. One study found that between 2017 and 2021, Americans on average were exposed to 350% more wildfire smoke than previous years. For communities with more people of colour and non-English speakers, this number was closer to 450%.

Fire pollutants can also travel long distances, riding the wind into highly populated areas hundreds of miles away.

“Urgent actions are required to address such substantial health impact and the associated environmental injustice in a warming climate,” such as more financial and technological support for communities and countries that are hit the hardest, the study concluded,

Climate Change

The study follows last year’s record-breaking fire season, with carbon emissions from all fires totalling 8.6 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide, 16% above average.

A report published in August attributed almost a quarter of this increase to Canada’s record-breaking fire season. Nearly 6,600 blazes burnt across 45 million acres, 5% of the entire forest area of Canada and roughly seven times the annual average, affecting 230,000 people.

Other large-scale fire events last year included wildfires in Greece, which were the largest ever recorded in the European Union, as well as fires in western Amazonia and northern parts of South America. The latter were driven by severe and prolonged drought conditions exacerbated by climate change, the report said. Among the deadliest events figured the Maui wildfires, which killed 100 people as they engulfed the historic city of Lahaina, destroying much of its homes, businesses, and the harbour, and fires in Chile, which claimed 131 lives.

The same report concluded that climate change increased the probability of high fire weather conditions, long-term average burned area, and extreme burned area during the 2023/24 season.

Climate change has increased the wildfire season by roughly two weeks on average globally, mostly by enhancing the availability of fuel through heat and dry conditions. The average wildfire season in Western US is now 105 days longer, burns six times as many acres, and sees three times as many large fires – fires that burn more than 1,000 acres compared to the 1970s, according to Climate Central.

Despite an increase in the frequency and severity of wildfires globally, however, the amount of area burned by wildfires each year has gone down over the last few decades.

A 2017 paper published in Science found that global burned area declined by approximately 25% over the past 18 years, despite the influence of climate. The phenomenon can be explained by a decline in burn rates in grasslands and savannas as a result of the expansion and intensification of agriculture.

The past nine years have been the hottest on record. 2023 was the hottest year globally, with global average temperatures at 1.46C above pre-industrial levels. 2024 is now on track to be even hotter.

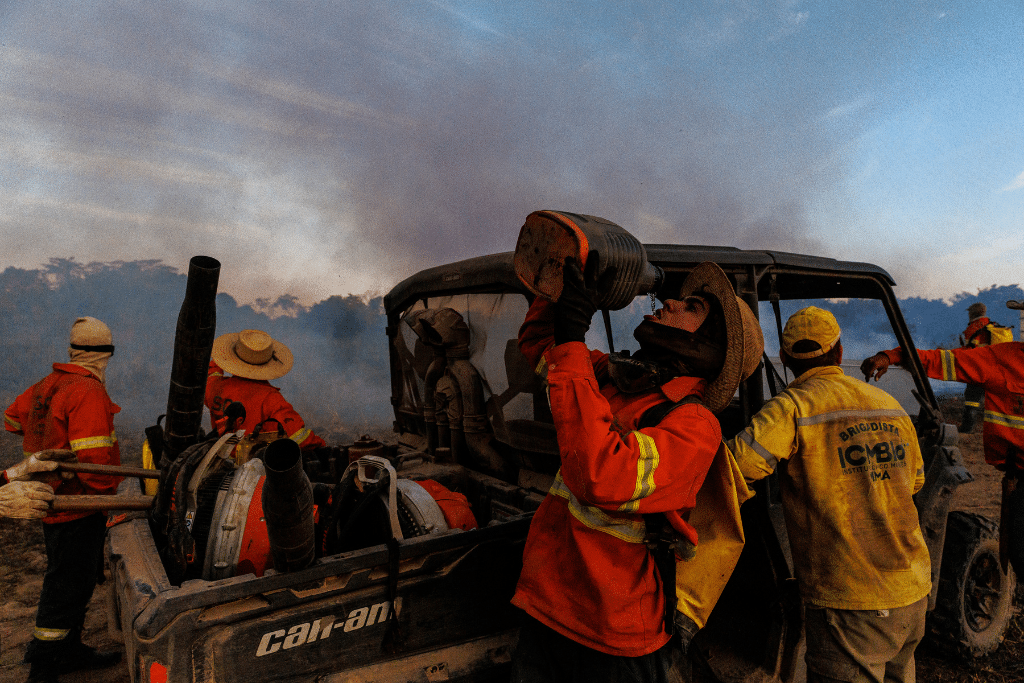

Featured image: Diego Baravelli/GRAB via Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF).

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us