There is something about the egg that is so rich and evocative to the human psyche. With its graceful, efficient, rounded compactness, and the subtle tapering of its form, eggs are so universally iconic that the word “oval” stems from the Latin ovum, or the product of an ovary. But for all its natural elegance and millions of years of slow evolution, today, the egg is at the center of a brutal, fast-moving, mechanized industry that’s anything but beautiful.

While you’re thinking about eggs, please consider Bean, a one-time prolific producer of them. Now living her best life in Thornton, CO, Bean is a rescued laying hen who was born for the express purpose of producing for the egg industry. But, lucky for her, she is now spending her days in view of the mountains at Broken Shovels Animal Sanctuary. Bean is four years old. She may live for another few months, perhaps a year at most. Bean’s food, medical needs, and quality of life are carefully attended to, but she is living with an early expiration date hardwired through intense genetic engineering and a rough start in life. In other words, Bean is like all other layer hens, except she has found sanctuary to live out the rest of her days.

Her short lifespan is something Andrea Davis, founder of Broken Shovels, is mentally prepared for, despite her affection for the hen. “We find that their bodies succumb to a variety of cancers despite reproductive interventions like implants and surgeries like hysterectomies,” Davis says of rescued layer hens like Bean. “They are bred to be frail, and many experience bones that break easily due to having calcium and mineral deficiencies before they were rescued.”

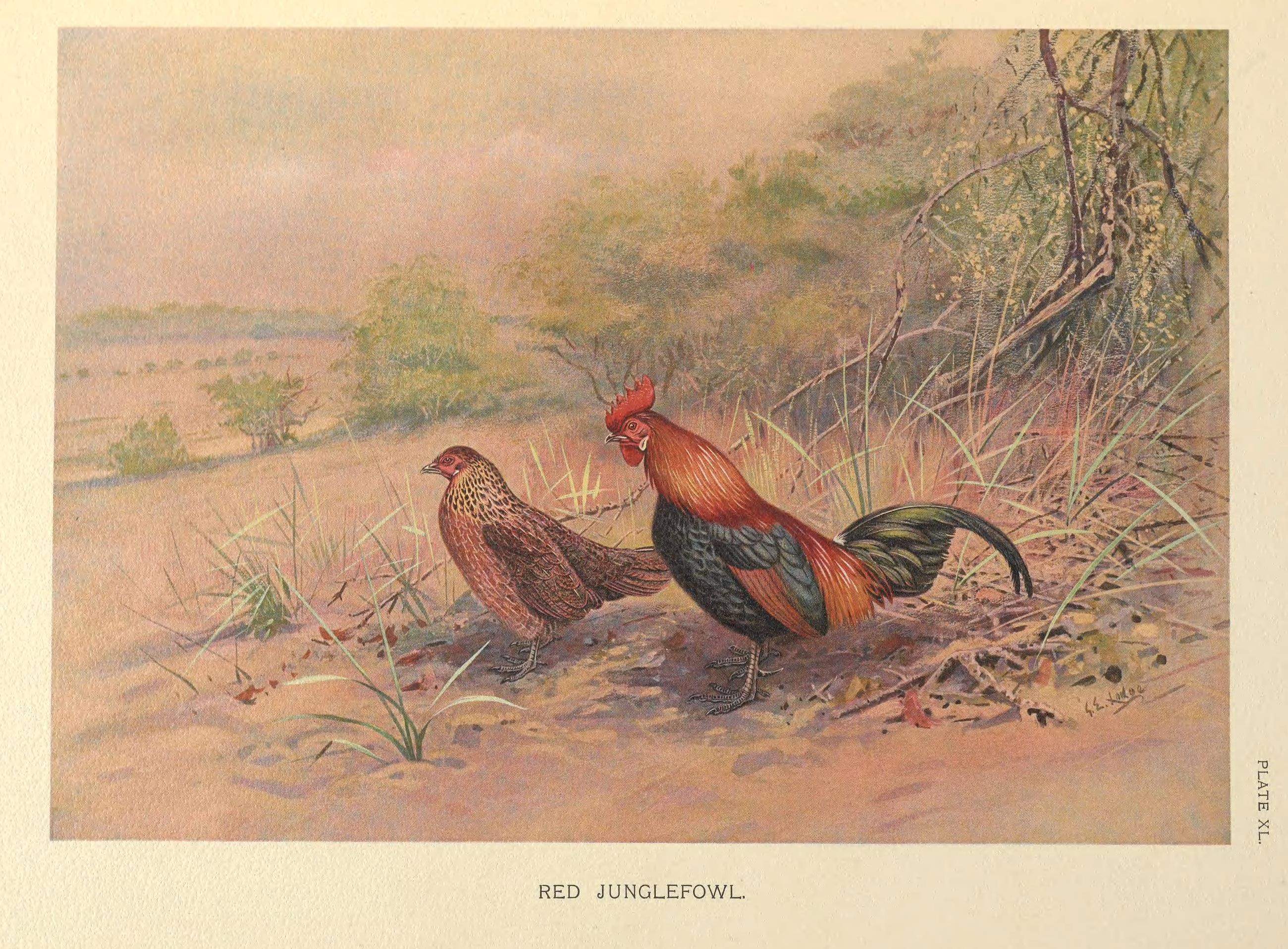

George Edward Lodge/Wikimedia Commons

George Edward Lodge/Wikimedia Commons

Where did chickens originate?

Next, consider the red junglefowl. It is likely that when you hear the word “egg,” the red junglefowl is central to what pops into mind next, whether or not you realize it. This bird is a direct ancestor of today’s layer hens.

A small, forest-dwelling bird of South and Southwest Asia, the red junglefowl was venerated for centuries for their vibrant plumage and unique vocalizations, including the distinctive, confident crowing of the males. The birds, which evolved from the pheasant about 6 million years ago, spread from Asia to Africa, the Mediterranean, and Europe along Silk Road trade routes—and excavated burial sites have unearthed junglefowl cockerels and hens alongside their human companions.

How did these jungle-dwelling ancestors become the virtual egg-laying machines that are so ubiquitous in the human diet today? Where there is a demand, there is a way. People have been eating the eggs of various species since recorded history, especially those of birds. Beginning in the 19th century, people started becoming very skillful at forcing as many eggs as possible from a laying animal’s body through selective breeding, manipulation, and scientific and technical innovations so that by the time the hen is slaughtered, her depleted body is considered “spent,” an apt phrase for what has been done to her by an industry focused on razor-thin profit margins and productivity. She has been spent and her body is often riddled with chronic, excruciating conditions as a result.

“Because of selection for increased egg production, these birds often develop problems of the reproductive tract and skeletal system, which are worsened by their living conditions. They most commonly die of a painful condition called yolk peritonitis, when a portion of the egg escapes the reproductive tract and ends up in the abdominal cavity, which is somewhat similar to ectopic pregnancy,” says Dr. Gwendolen Reyes-Illg, veterinary advisor of the Animal Welfare Institute. “They may also suffer from prolapse of part of their reproductive tract, which can lead to cannibalism by other hens, especially in crowded conditions.”

Djordje Vezilic/Pexels

Djordje Vezilic/Pexels

The truth about chickens in factory farms

Red junglefowl are about one-third the size of the hens like Bean who are used in the egg industry today. Unlike their wild forebears, who produce at most 30 eggs per year in the spring and summer months, the domestic layer hen may lay nearly 300 eggs annually, according to United Egg Producers, contributing to the almost 97 billion eggs produced each year in this country. Half of those eggs contain male chicks and, being worthless to the egg industry, they are killed as soon as their sex is roughly determined shortly after hatching. Any method of killing the male chicks—from being ground alive, incinerated, crushed, drowned, or gassed—is legally acceptable.

The first commercial incubators in the United States were developed in the middle of the 19th century, and these early machines, which allowed for hundreds of eggs to hatch at a time, were further developed into industrial incubators by the end of the century. With that, the backyard chicken scratching in the dirt who laid eggs for a family was already beginning to seem like a relic of the past: incubators that were capable of hatching 20,000 eggs in one setting were part of what paved the path to the concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) of today.

Starting at a hatchery, where the collected eggs are taken after their mothers lay them, they roll onto conveyor belts, and are then stored in an environment controlled for temperature and humidity for up to seven days before being transferred to an incubator with hundreds or thousands of other eggs. Around the 21st day after incubation, the birds hatch, surrounded by hundreds of newborns, and not a mother hen in sight.

If allowed to protect the eggs in her nest, a hen’s dedication to her job is the stuff of legend. The expression “mother hen” is construed today as someone who is overly worried and controlling, but it is borne of the bird’s deep, unwavering protection of her progeny, whether in egg or chick form, against even the most fearsome of predators. The eggs that hatch in incubators never receive this loving protection. This is true of birds who are raised in CAFO settings as well as backyard birds and so-called free-range chicks: the vast majority begin their lives in industrial incubators like Bean, not in a nest looked over by a watchful mother hen.

When she was just within her first week of life outside of the protection of her shell, Bean would have had her beak cut, which the industry euphemistically refers to as “trimming,” but is actually an amputation of the end of the beak with a hot blade or infrared light. She would have not received numbing agents or follow-up care. At about 18 weeks of age, these birds will be considered mature, and sent to produce eggs for the remainder of their lives, their beaks mutilated.

Thành Đỗ/Pexels

Thành Đỗ/Pexels

“Chicken beaks are complex, highly innervated organs that can sense touch, pain, temperature, and even magnetic fields. Birds use them for manipulating food, exploring, interacting with other birds, and preening,” says Reyes-Illg. “In addition to causing pain, beak trimming is suspected to result in a loss of sensory ability and ability to orient in the environment, since this relies on sensing the earth’s magnetic field. Beak-trimmed birds can’t preen as well, so they develop more problems with ectoparasites.”

This practice is done routinely by egg and bird-meat industries to reduce the likelihood of aggression and cannibalization between the stressed, crowded chickens. Even when beaks are not cut, Reyes-Illg notes that cannibalism and injurious pecking still happens due to the systemic conditions of the industry, like overcrowding and their inability to express natural habits.

Despite her early start, Bean is extremely lucky. She was rescued as part of a coordinated effort that took place in May of 2020, when a single egg facility housing 100,000 hens in Iowa “de-populated,” or culled, the birds earlier than expected due to a worker shortage in the early days of the pandemic. Nearly all the hens were killed at the facility, but Bean and 34 other birds were rescued and taken in by Broken Shovels, where they were able to live somewhat of a natural life and express innate habits for the first time.

“It felt both tragic and beautiful seeing the first time they could dust bathe, perch, scratch at dirt, peck grass, or eat fruit and vegetables,” Davis of Broken Shovels says. “I can’t count how many times I broke down sobbing while watching these girls experiencing the real world outside of a cage for the first time, and to see their instincts and natural joy pour out of them.”

Peter Werkman/Unsplash

Peter Werkman/Unsplash

Cracking the egg

According to the USDA, more than 81 percent of all US layer hens today live in environments with more than 30,000 other birds, and many of these operations hold hundreds of thousands of hens in one football-field-sized structure. In Iowa, where Bean lived, the human population is just over 3 million. There are over 45 million hens in Iowa alone, and about 390 million layer hens in the United States at any time.

In order to coax more product out of the hens, the industry uses a practice called forced molting, in which food and water are withheld and access to light is diminished for a period of one to two weeks, after which time egg production is accelerated briefly. The hens will go through this experience up to three times before they are considered more valuable dead than alive, and are consequently slaughtered.

After about 18 months, a hen is generally considered spent, as she is no longer producing a high volume of eggs. At this point, she and others like her will be collected for transport and slaughter, first by a “catcher,” who grabs up to four hens at a time and carries them upside-down by their fragile legs to be tossed or dropped into transport crates. Speed and efficiency are what matter here, and according to one study, nearly 30 percent of hens had broken bones after transport. Exposed to extreme temperatures of heat and cold on their way to the slaughterhouse, the hens continue to endure the stress of being crowded as well as noise and motion, not to mention aggression from other agitated birds. The small slats of the transport truck are likely to provide the first and last time most will breathe fresh air or feel the sun. Only a small number of slaughterhouses in the country accept spent laying hens, so the birds may be transported many hours, deprived of food and water.

Birds, which make up more than 98 percent of the animals killed each year for food, are not covered by even the exceedingly low standards of the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act. Most commonly, though, at the slaughterhouse, workers will unload the crates of hens, then they will be quickly hung upside-down in metal shackles and moved by conveyor through an electrical water-bath designed to stun them. Still upside-down on the line, an automated knife will cut their throats. They will bleed out, until they are dragged through the scalding tank, after which their lifeless bodies are plucked. Even though they were not raised as broiler hens, their bruised and damaged flesh still has some value to the industry, so it is often shredded or diced for the companion animal food industry or used in cheap canned products. The red junglefowl may live to 20 years of age. A rescued bird like Bean may live up to four or five at a sanctuary.

Yo! Egg

Yo! Egg

What are vegan eggs?

Does all this suffering and destruction have to be the way to an egg, though? As interest in plant-based foods has grown steadily, so too have innovations to meet that demand. While vegans have replaced eggs in cooking and baking with everything from tofu to applesauce, now there are easy one-for-one replacements on the market that take the guesswork out of cooking and baking without eggs. Ener-G Egg Replacer has been on the scene for decades, but consumers today have more options, like the mung bean-based JUST Egg in liquid and prepared forms as well as powdered VeganEgg by Follow Your Heart for baking or savory applications. This year, Israel-based Yo! Egg wowed the crowd at the National Restaurant Association Show in Chicago with its sunny-side-up and Hollandaise vegan eggs, complete with gently crisped edges and an actual yolk that runs when pierced. Just as the plant-based dairy and protein categories are bursting at the seams with innovative, delicious options, the egg sector is just beginning to take off, and not a moment too soon.

These days, with the loud, crowded facility in Iowa long behind her, Bean has distinguished herself as a self-appointed seeing-eye hen at Broken Shovels. She is wary of people but loves being helpful with her sister hens who have lost some or all of their eyesight and are grouped together. Blindness and vision loss are common with these birds who were once trapped in enclosures with high levels of ammonia. Bean is the only fully-sighted bird with that flock at the sanctuary. She has found her place.

“Her pecking noises let them know where to go to eat, and she guides them into their coop at night,” says Davis. “Bean is a very special hen.”

For more on plant-based eggs, read:

JUMP TO ... Latest News | Recipes | Guides | Health | Shop